… so that thinking can change direction. As beautiful as this saying is, it often undercuts its little ugly brother „thinking in circles“, or also: thinking in silos.

Why silos of all things?

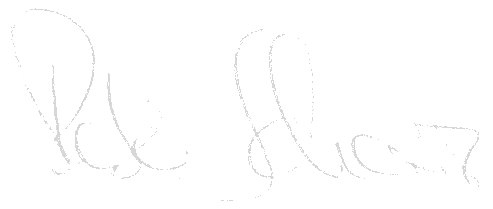

Silos are per se something very useful, since in an abstract sense they serve to store and protect work results. In the corporate context, work processes and their resources are also separated with the help of silo areas. The clear separation of the company into areas of responsibility makes it possible for the management level to control the company’s divisions.

Thinking in silos is now a metaphor for corporate divisions that are organized – mostly implicitly – like silos, standing next to each other with a considerable distance between them and protecting their contents. The three keywords for the negative connotation are:

- considerable distance: no connections between each other

- stand: no movement towards each other or in the same direction

- Protect content: no transparency, no exchange of information

The picture is of course exaggerated; the legal requirements (consolidation), the self-interest of capital providers (annual report, strategy meetings) as well as the necessities of service provision (planning, purchasing, production, sales) require a certain degree of interaction and information. Nevertheless, all management levels (strategic, tactical and operational) remain inefficient if the interdisciplinary exchange is limited to the absolute minimum.

What exactly is the silo problem?

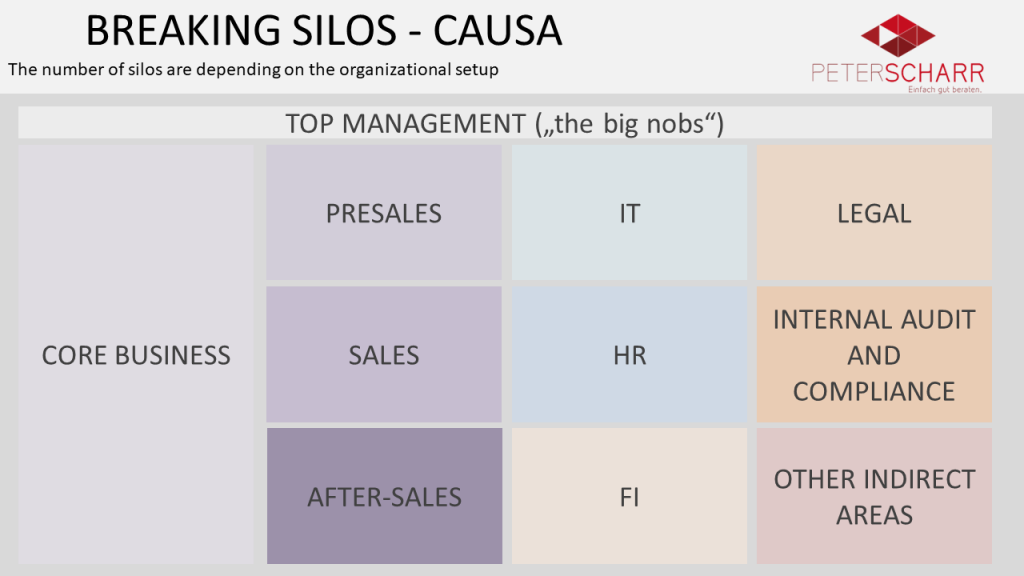

As a company grows, one very crucial criterion for success is increasingly jeopardized: the internal transparency of service delivery. In a company with 15 employees, every employee knows all the customers and the boss, the processes and their complexity are manageable, and everyone can see when their colleague is already working overtime again with the month-end closing.

If the company now grows organically or with a powerful M&A, then this nest warmth is no longer given for long. This is exactly where silo thinking begins. Since processes, specifications and the names of colleagues from other departments are no longer familiar, they are ignored and understanding of them is lost. Trust disappears, rumors are overrated and generalized.

The black box of the „foreign“ divisions appears impenetrable, sometimes even threatening – but in any case more complicated than necessary and completely oversupplied with regulations and resources. Because the others seem to stand so vehemently in the way of one’s own success and that of the company, people begin to distance themselves. As a result, cooperation decreases, cross-functional collaboration becomes costly, and overall performance deteriorates.

Interestingly, poor performance is both a symptom and a cause. The insinuation that „they’re not doing their job over there“ doesn’t have to be true at all; if this culture isn’t consistently corrected, overall performance actually drops. Everyone suspects a problem, and doesn’t want to be on the wrong side when it comes to light.

The risk of silo thinking exists in all organizations, but increases with their size and age. It emerges more often in organizations that have grown slowly (decades), as here the foundational apathy is often long dead, while the expectation for the boss to be hands-on remains.

If these employees are not consistently engaged in development by leadership, the negative effect is not negligible – McKinsey describes in its Five-Fifty on Silos that silo thinking can significantly impact an organization’s performance.

Declaring war on silos

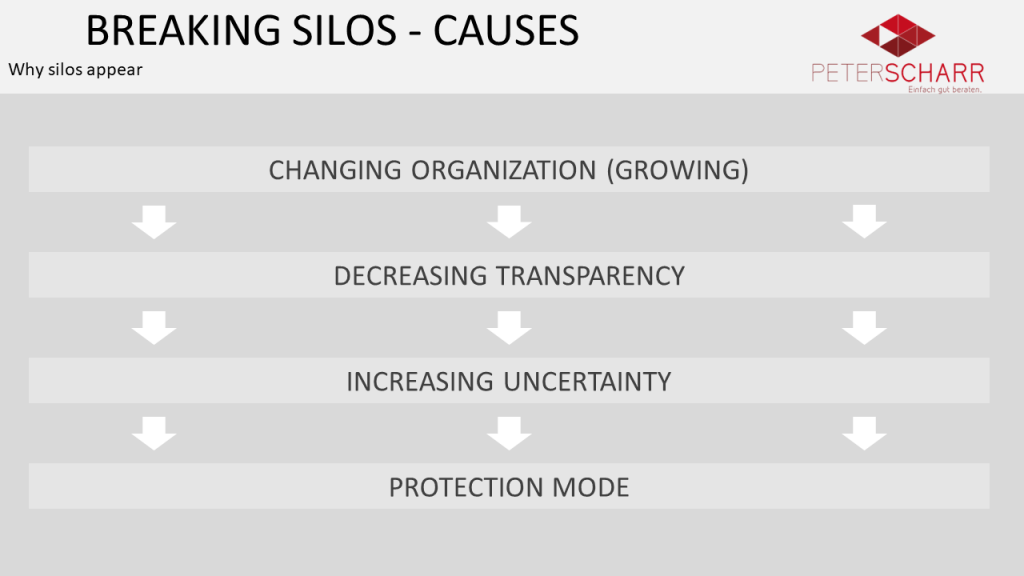

According to Forbes, the problem doesn’t originate at the operational level, but at the very top. Silo thinking is also less of an organizational problem and more of a cultural one. Therefore, the key is to change the culture. Since silos provide structure, the focus is not on eliminating organizational divisions, but on strengthening transparency and collaboration between them.

This is achieved primarily by creating a shared view of the corporate task.

Interestingly, poor performance is both a symptom and a cause. The insinuation that „they’re not doing their job over there“ doesn’t have to be true at all; if this culture isn’t consistently corrected, overall performance actually drops. Everyone suspects a problem, and doesn’t want to be on the wrong side when it comes to light.

The risk of silo thinking exists in all organizations, but increases with their size and age. It emerges more often in organizations that have grown slowly (decades), as here the foundational apathy is often long dead, while the expectation for the boss to be hands-on remains.

If these employees are not consistently involved in development by management, the negative effect is not negligible – McKinsey describes in its Five-Fifty on Silos that silo thinking can significantly impair the performance of an organization.

Top Management – The Company and its Markets

Top management sets the path in the form of a long-term strategy for the company as a whole. In turn, the company’s performance is essentially defined by the markets in which it operates. This includes not only the market for sales, but also, among others, the market for suppliers, the personnel market and the market for financing. It is the responsibility of top management to regularly communicate to all areas and levels an appropriate level of detail on the situation in these markets. This strengthens the sense of the company and its own contribution to it. The objectives for mid management need to be carefully balanced – „Up to where is it promoting performance, and from where do I reward booting out other areas?“

Upper and Mid Management – The Leadership Culture

It is the task of managers to achieve the goals set from above within the given framework. The pursuit of these does not always succeed with a sufficient degree of foresight. It should be made easier for executives to regularly gain insight into the affiliated divisions and regions. This can take place in the form of round tables and workshops, or organizationally and invasively, for example through job rotation or greater weighting of corporate goals in the objectives. This should serve to mentally and physically leave one’s own haze and gain valuable experience and contacts within the organization. The insights gained are then to be communicated to the company’s own employees.

The business – organization and operations

The culture of the operational level can be strengthened formally and informally. Formally, processes should be designed to be consistent, accessible to other areas, and easy to read. Application environments, where not critical, should provide broad rights to look around. The database for central entities (customers, suppliers, partners, etc.) should be kept consistent and available in a regulated MDM process. Cross-divisional projects should be encouraged. Overarching responsibility for results and processes, which strengthens networking and coordination, should be extended. Since both project and line work take place at the bottom of the food chain, top management must ensure that targets are met and that any decision-making needs are addressed quickly.

Forewarned is forearmed

Of course, none of these undertakings is easy to implement. Many employees have grown up in the existing culture and become successful as managers or specialists. They identify with the previous way of thinking and acting. Often, this attitude is accompanied by a considerable fear of exposing themselves, as Process Cafe describes. The success factors for such a „mindset change“ are thus at least as challenging as for other change projects:

- Set clear goals

- Involve management

- Structure the project

- Communicate permanently

- Measure the success

This turnaround will not work for all employees. You should be prepared for situations where the company changes direction but not all employees can follow. When all attempts fail, sometimes it’s time to go separate ways because a shared future is no longer possible under the changed premises.

A company is well advised to constantly redefine itself on the path to growth, not only in relation to customers and suppliers. Organizationally, too, care must be taken to ensure that all levels can follow the – sometimes lurching – course. To this end, it is also necessary to regularly listen to employees and managers using suitable survey techniques and to respond to their answers.

In this way, it may be possible to prevent the emergence of silo thinking before it has taken hold.

Good luck with this,