Headless actionism is the most common reaction to escalations. But escalations are extremely useful, and in most cases they can be prepared very well. At least if it is possible to work out structured solutions out of the chaos that is often initially present.

Escalation in the sense of an operational or project problem should be understood here as the raising of an issue from one level to a higher one (up to top management). A deviation from the planning can therefore no longer be caught at one’s own level; a decision usually has to be brought about. Accordingly, one turns to a higher decision-making level with the request for support because one lacks the competence (knowledge and/or ability) to solve the problem oneself.

A good escalation

Even if „A good escalation“ sounds like a contradiction in terms at first, the formulation reveals a certain logic after a closer look.

Why is there escalation? Because decisions are needed that prevent a problem (in advance) or eliminate it (in the near future). So the content of an escalation must be primarily the support of this needed decision. And this can be done in a sensible or a less sensible way.

Against this background, the main task is information collection and processing. The management (especially at the top) often has little insight into operational or tactical problems, while their colleagues are usually strategic according to their function. To enable them to make a well-founded decision, you should first determine the facts and then prepare them in a „management-friendly“ manner. The time you have to do this depends heavily on the risk / problem in question.

Of course, in a few individual cases, this information gathering and dissemination is exhausted by a simple „There’s a fire!“. In the vast majority of cases, however, it is a bit more complex, and therefore a bit better to prepare. It is good for those who take the time to first look at where exactly the problem lies.

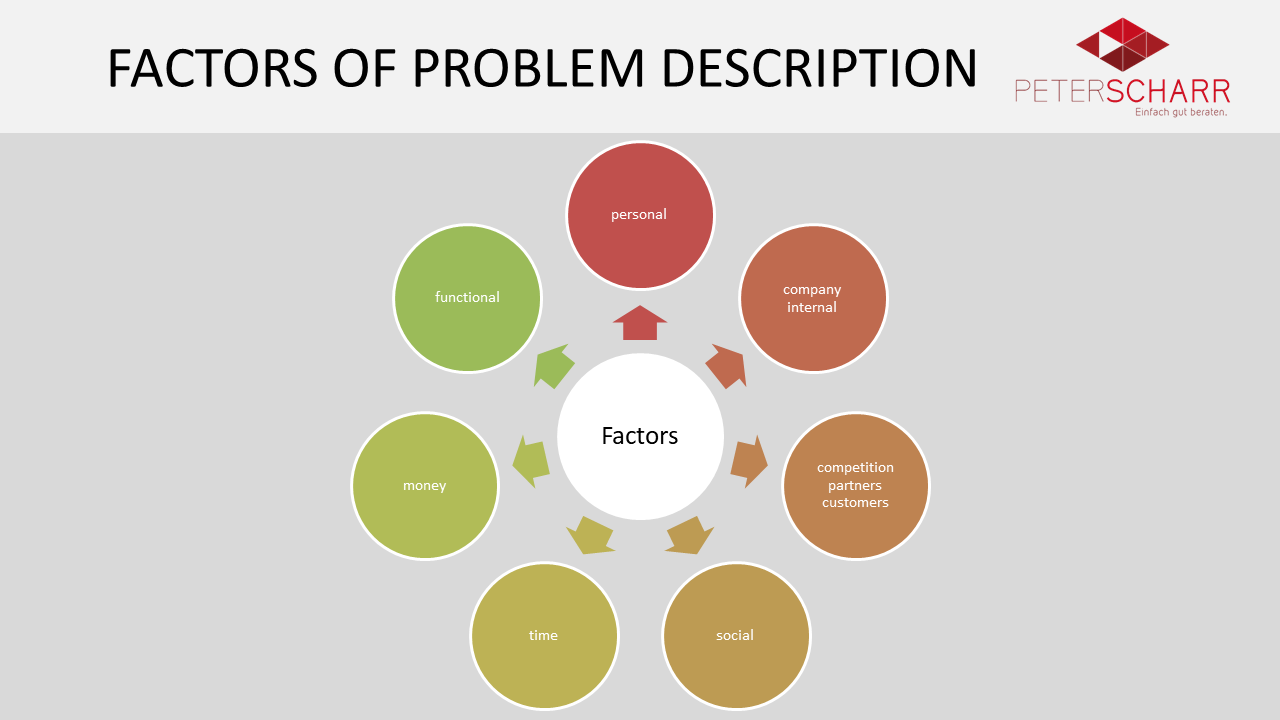

For the preparation of an escalation, a number of information areas need to be checked first, e.g. the following, depending on the context.

The classic project planning factors (the three on the left) are supplemented here by several levels that describe organizational and market/social levels. This is because the planning slippage can also affect levels that are actually outside the project or operation.

For the description of these factors, the criteria and methods of risk management can be used wonderfully. The topics of escalation management and risk management are closely linked anyway, since risk management ideally recognizes whether an escalation is necessary or not before a problem occurs.

A risk is described by the combination of a probability of occurrence and an expected amount of damage. The assessment of the risk is derived from this. Since the amount of damage is usually expressed in monetary terms, but this is a bit too short in our context, I generalize this to „expected damage for the respective area“. Once the probability of occurrence and the expected damage have been sufficiently determined, the options for pulling the baby out of the well can be illuminated very well from there.

Once you have created this problem description together with other experts, don’t forget middle management. Affected group, department, division and regional managers will also want to be involved when it comes to presenting a major problem to top management. If everyone is on board, they’re already halfway there.

What if it’s just fuming?

So meaningful escalation is a lot more diligence and communication work than you might think. In return, one is usually provided with a gratifying amount of freedom of movement, and problem situations can be identified and dealt with in advance. In problem prevention, we actually move into risk management, describing risks and clarifying the appropriate mitigations (cost, time, scope).

So you see a problem coming to the organization, and you set out to determine the potential impact on those factors in terms of probability and damage impact. From this point, you then brainstorm (often with designated subject matter experts) to identify possible countermeasures.

The measure itself, of course, again has costs, time requirements and scope – and of course (that’s why they do it) – effects on the other factors. These don’t always have to be consistently positive. If you present a mitigation, it will hopefully eliminate the risk, but it will also cost money and time. Therefore, you will almost never be able to make proposals that have only positive effects.

So it will also not be a no-brainer for the person in charge to make the needed decision. It is in most cases a weighing between different alternatives. It is up to you to identify and present the impact of those alternatives, and up to the decision maker to make the needed decision based on that information.

Probability is deliberately neglected in my example, as these estimates are often little more than gut feelings. There are things that are very likely without being facts (these could be marked in bold in the table above, for example). Very unlikely consequences, on the other hand, would only be listed if the expected damage is sufficiently large. In all other cases, you need to ask yourself where exactly the difference is between a 37% and a 33% probability, and what concrete impact this difference must have on the decision. If you need it to be more precise in your specific environment, then feel free to plan more precisely.

The cobbler and his shoes

Why can’t the experts actually make the decision on their own right away? Well, basically everyone can make the decisions (even a passer-by who is tying his shoe in front of the company premises). But why not let him do it?

Because he usually does not have the necessary information and the right priorities to make the decision in the best interest of the company. And – let me be stoned for saying this – the individual specialist often feels the same way. When a decision has to be made, the goal is to find the option that promises the greatest possible added value (or the least possible damage). This added value, however, depends on the information that flows in and the priorities that I set.

This is why decisions are delegated upwards in the first place – the experts with different levels of information and priorities could not agree on one option. The popular motto in large organizations, „Reporting makes you free,“ applies here. Of course, the organization itself should always strive to make decisions as close to the grassroots as possible to avoid delays and sprawling complex processes. But if a consensus cannot be reached at one level, the next higher level must be involved.

What the experts can do, however, is to make recommendations in addition to describing the options. If there is expert agreement, a single option can be singled out as „preferred“ (very good). If there is disagreement, highlight 2 or 3 of the options as respective recommendations if necessary (still better than no recommendation at all). This is also part of the important information for the person in charge: Which option is actually preferred?

But what to do if there is a fire?

The previous descriptions assume that there is still time to analyze problems and prepare decisions. In most cases this is true. The real fire case is the case that is felt and lived in 99% of the cases, but that is actually present only in 1% of the cases.

But if we have a fire case (e.g. immediate danger to life and limb, a loss of production, massive loss of company assets is imminent, etc.), decisions and action must be taken quickly and in a solution-oriented manner. The danger is that because of the urgency, there is not enough time to gather information on which to base decisions for good firefighting. So instinct and experience come to the fore when things really have to happen quickly. The escalation itself is often only information (the aforementioned „There’s a fire!“), because – if there are no correspondingly sophisticated emergency processes – there is often no time to quickly involve other decision-making levels.

So if there really is a fire, inform those affected and the decision-makers and eliminate the immediate danger of damage occurring. Once this has been done, make sure that the analysis of the factors described above is carried out afterwards. A corresponding RCA (Root Cause Analysis) should not only describe where the problem lay. It also needs decision templates to prevent a recurrence, or to repair the damage already done.

According to modern error management theory, it is actually no big deal if an error happens once. However, it becomes difficult when the same error occurs several times and the organization is not able to prevent this recurrence. So the rule here is „make mistakes, and learn from them!“.

Bringing the issue to a close

Despite the very constructive description here of how to deal with escalations, of course no one likes them anyway. Therefore, today there is often the awareness that an escalation process should be set up, but everyone is also anxious to bring these escalations to an end as quickly as possible. It is not a classic business or project business after all.

What is the best way to proceed? Assuming the fire is not burning (anymore), you have gathered all options, considered impacts and determined a recommendation. Now identify the decision maker(s) and inform them, e.g. in a short 1h meeting (send slides in advance). A short problem analysis with presentation of the options and subsequent room for questions / discussions will in most cases already bring you the decision. This decision must be documented and communicated to all participants. In this way, you create commitment and avoid misunderstandings.

If the decision is particularly delicate, it is advisable to involve the key decision-makers before the meeting. In this way, you can clarify questions in advance and avoid discussions during the main meeting.

The next steps depend on the decision. If it is a new activity, you will very often set up a project based on your preliminary plans. If it is a direction correction, you will work with those affected to incorporate the decision into existing planning.

In both cases, it is often necessary to actively inform those indirectly involved about the changes. So don’t forget your stakeholders, and make sure that in the end not only the problem has been solved / prevented, but also all involved, affected and interested parties are informed about it.

In this way, you should be able to let a lot of unproductive steam out of the boiler, making goal achievement more likely.

Good luck with this,